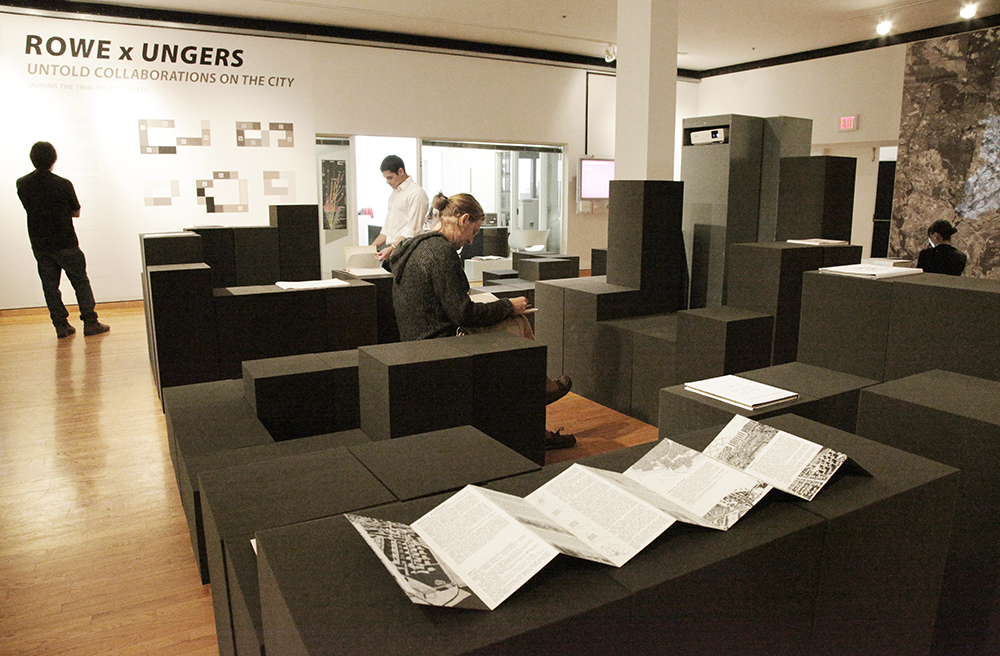

Location: Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art and Planning, Hartell Gallery, Ithaca, USA

Program: Research and Exhibition

Dates: August 25th – September 3rd, 2009

Status: Exhibition for the 2009 Preston H. Thomas Symposium “Shaping Architects = Shaping Architecture”

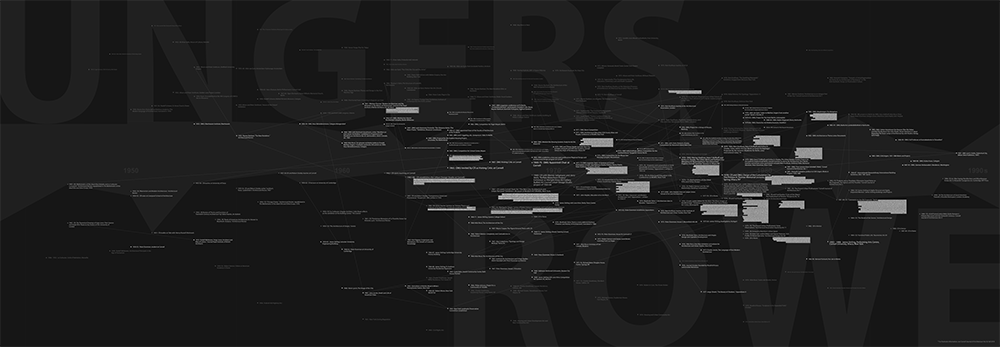

Extensive architectural research and assessment have separately addressed the work of Colin Rowe and Oswald Mathias Ungers. Now, as the profession is in a constant search for tentative alternatives, a comparative understanding of Rowe and Ungers’ impassionate pedagogical discourse within the turmoil of their time permits us to refocus on important issues of architecture and the city relative to the pedagogical goals being pursued at Cornell during 1960-70s. Latent collaboration and competition marked the period when Rowe and Ungers both taught at Cornell. Due to bureaucratic situations and institutional grievances, the relationship has not been recorded as being mutually profitable. But the state of confusion in which architecture existed in this tumultuous period — not dissimilar to the discipline’s current cacophony — allowed for a common aspiration and rigor in promoting a theory of architecture that envisioned new methodologies and modes of thought. Despite the infamous stories of conflict, it is more important to note their mutual understandings of critical conditions for architecture, and the urgency to establish new grounds for projective productions.

As a visitor to Cornell University, Department of Architecture, one cannot escape the mysticism and folklore surrounding the stories of Colin Rowe and Oswald Mathias Ungers during their period of co-habitation on this remote plateau of academic bliss. The ghost of the two figures lurks behind every corner and every encounter. The extraordinary stories of personal escapades and incidental conflicts are relished as part of the school’s legacy and continue to hold ground as part of institutional history. What exactly happened during this period of coexistence to have produced such productive influential work persists as an irresistible project of pedagogical archeology.

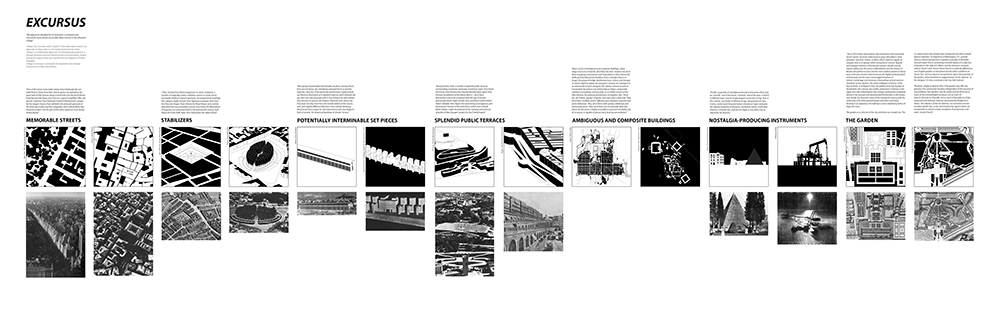

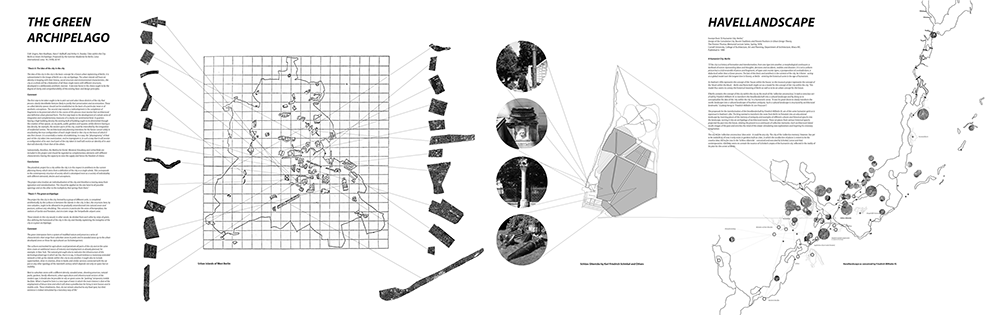

A comparative understanding of their work is significant for us today for several reasons. Theoretical armatures were constructed through the disciplinary languages of architecture as a means for exploring a mode of operation resistant to, yet critical of the political, social, economic, cultural turmoil of the period. To project beyond the reclusive banality of the picturesque and sci-fi utopianism, they sought a disciplinary autonomy that would actively engage, not ignore, society in the conceptualization of architectural languages through the city. Their methodologies were based on extensive research and analysis, processed through iterative adjustments of pedagogical frameworks. Studio and thesis projects became laboratories of larger experiments and publications and exhibitions were utilized as tools of analytical production. Crutially, architecture and the city were understood as flexible systems in constant flux. Rowe and Ungers shared the aspiration for an alternative path between the ideological resistance of the existing city and the authoritarian trauma of modern planning. Urban strategies were deployed as malleable mechanisms in which object and field were in continuous dialogue and as network systems which accommodatied the inevitable changes and transformations of urban conditions.

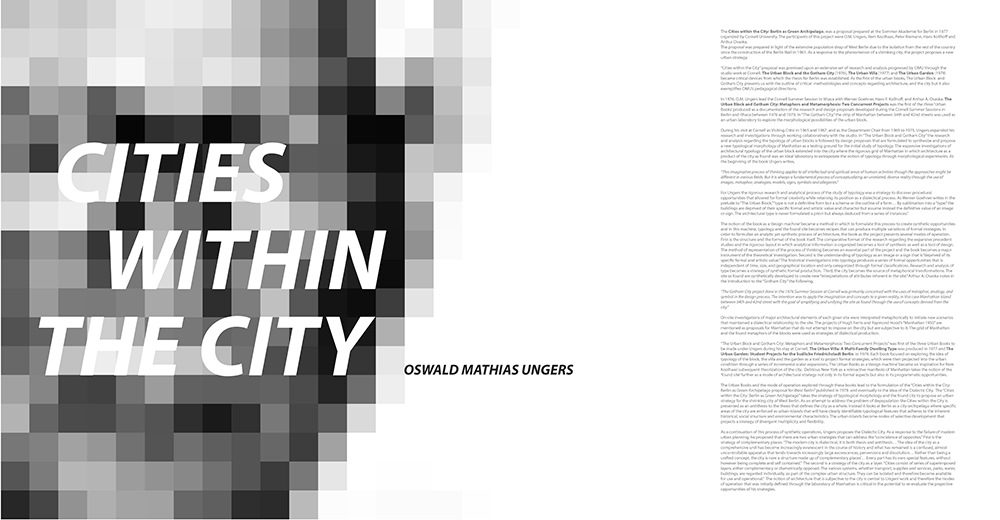

Take for example, Rowe’s proposal for Harlem in Upper Manhattan in The New City: Architecture and Urban Renewal Exhibition at MoMA, New York and Ungers’ proposal for the area between 32nd street and 42nd street in The Urban Block and Gotham City: Metaphors & Metamorphosis. The two projects, executed in 1967 and 1976 respectively, utilized Manhattan as a site to test the latest theories on the identity of architecture and the city. Although the projects are almost a decade apart, both works were an attempt to address the overt anxieties of new development and construction against the urgency of the imminent disappearance of the existing city. In the 1960s, Manhattan was experiencing the biggest construction boom since the 1930s. Massive redevelopment was accompanied by large-scale destruction. It was a period of internal conflict in which new mega-developments were being realized alongside discussions regarding the history, architectural heritage, and preservation of the existing city fabric. In 1961, the new zoning law took effect, which encouraged an “open” city idea, reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin of 1925. The Late Modernism of the 1950s was being amended by Historicist Modernism exemplified in projects such as Philip Johnson’s New York State Theater at Lincoln Center in 1964, Edward Durell Stone’s Gallery of Modern Art in 1964 and Minoru Yamasaki’s World Trade Center Towers in 1973. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, Jane Jacob’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities was published 1961, and with the establishment of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965 and the gradual waning of the legacy of Robert Moses, preservation of the traditional scale and character of city street life became an essential part of the discourse surrounding architecture and city planning. In this context, Rowe’s Collage City and Ungers’ Cities within the City became projective manifestos to test and investigate the new directions in architecture and city that were critical of the disciplinary anxiety of the times and proposed an urban vision for the new collective. This is what remains pertinent to us now.

If the decades of the 1960s and 1970s are recognized as a period when modernist ideals were questioned and the profession was infused with self-doubt, we find ourselves in a similar situation today, as the practice struggles to identify its position within the multiplicity of aphasic spectacles and the discord of heterogeneous complacencies. In this sense the critical modus operandi of Rowe x Ungers can be regarded as a tool for re-engaging and critiquing the discipline in its current state. To know what is to be, we need to know what was before.

Notes:

[1] Anthony Vidler, Histories of the Immediate Present: Inventing Architectural Modernism, (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2008), 114-115; Rem Koolhaas and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Interview with O.M. Ungers,” Log, Vol. 16, Spring/Summer 2009, 57-58.

[2] Colin Rowe, As I was Saying: Urbanistics, ed. Alexander Caragonne, Vol. 3 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 2.

[3] Anthony Vidler, 169-170.

[4] Rem Koolhaas and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, 59-60.

[5] Rem Koolhaas and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, 67.

[6] Colin Rowe, As I was Saying: Cornelliana, ed. Alexander Caragonne, Vol. 2 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 75-78.

[7] Museum of Modern Art, The New City: Architecture and Urban Renewal, (New York: MoMA, 1967)

[8] Colin Rowe, Werner Seligmann and Jerry Wells, “Buffalo Waterfront Project” Exhibition Catalogue, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo NY, 1969; O.M. Ungers and Tilman Heyde, Lysander New City: A Project of Fourth and Fifth Year Students, Cornell University, Dept. of Architecture, Ithaca NY, (1970)

[9] http://www.team10online.org; Colin Rowe and O.M. Ungers Papers, Documents from Cornell University Dept. of Architecture Archives

[10] Colin Rowe, “Introduction,” Five Architects: Eisenman, Graves, Gwathmey, Hejduk, Meier, ed. Arthur Drexler, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 5.

[11] O.M. Ungers, Architecture as Theme, Lotus Documents, (New York: Rizzoli, 1982), 115-117.

[12] Colin Rowe and Judith DiMaio, “The River: Images of the Mississippi” Exhibition, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, (1976)

[13] O.M. Ungers, Werner Goehner, Hans F. Kollhoff, and Arthur A. Ovaska, The Urban Block and Gotham City: Metaphors & Metamorphosis: Two Concurrent Projects, Cornell Summer Session in Ithaca NY, (1976)

[14] O.M. Ungers, Hans F. Kollhoff, and Arthur A. Ovaska, The Urban Villa: A Multi-Family Dwelling Type, Cornell Summer Academy 77 in Berlin, (Cologne: Studio Press for Architecture, 1977)

[15] Colin Rowe, Peter Carl, Judith Di Maio and Steven Peterson, “Roma Interrota: Nolli Sector,” Architectural Design Profile, Vol. 49, No. 3-4, (1979)

[16] Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1978); Colin Rowe and O.M. Ungers Papers, Documents from Cornell University Dept. of Architecture Archives

[17] Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City; O.M. Ungers, Hans F. Kollhoff, and Arthur A. Ovaska, The Urban Garden: Student Projects for the Sudliche Friedrichstadt Berlin, Cornell Summer Academy for Architecture 78 in Berlin, (Cologne: Studio Press for Architecture, 1979)

[18] O.M. Ungers, Rem Koolhaas, Hans F. Kollhoff, and Arthur A. Ovaska, “Cities within the City: Berlin as Green Archipelago,” Proposals by the Sommer Akademie for Berlin, Lotus international, Lotus 19, (1978), 82-97.

[19] O.M. Ungers, The Urban Garden

[20] Colin Rowe, “Summary and Conclusion,” and O.M. Ungers, “A Humanist City: Berlin,” in Design of the Cumulative City Symposium Catalogue, The Preston H. Thomas Memorial Lectures, Spring 1978, (Ithaca, NY: Dept. of Architecture, College of AAP, Cornell University, 1999)

[21] Colin Rowe, “Comments on the IBA Proposals,” As I was Saying: Urbanistics, ed. Alexander Caragonne, Vol. 3 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 221-242; Rem Koolhaas, “Toward the Contemporary City,” Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995, ed. Kate Nesbitt (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 329.

* All images included in the timeline are courtesy of The MIT Press and the O. M. Ungers Archive.

Project Team

Project Director: Yehre Suh

Project / Research Assistants: Michael Esposito, Sophie Hochhausl, Armando Rigau, Rex Yau